Death Of Neil Stonechild - Timeline

November, 1990 was a bitterly cold month in a bitterly cold winter; five people, including teenagers Stonechild and Webb, froze to death within a 60 mile radius of the Saskatoon city centre in the winter of 1990/91. The night of November 24-25 was the coldest day that month. In fact, the 17 coldest temperatures recorded at the airport that month were the 17 hourly temperature measurements from 8:00 p.m. on November 24 to noon on November 25. Neil Stonechild died during this 17-hour period.

Neil was a wanted fugitive who had failed to return from an unsupervised day pass to a youth detention home, where he was serving a juvenile sentence for break-and-enter. There was a Canada-wide warrant for his arrest. He had been “unlawfully at large” (UAL) for eleven days when he and a friend, 17-year old Jason Roy, went out drinking, downing a 40-ounce bottle of hard liquor between them. At some point in the evening, they quarreled and parted company; Neil wanted to find an ex-girlfriend, Lucille Neetz, and apparently patch things up. She, however, was in a new relationship with a man named Gary Horse (whom she subsequently married), and wanted no part of Stonechild. Neil had learned earlier that day that Lucille was baby-sitting for her sister that night. When Lucille’s sister’s boyfriend, Trent Ewart, called the police, Stonechild apologized and left.

Constables Larry Hartwig and Brad Senger were working together for the first time that night. On their first call working as a team, at 10:59 pm, they may have saved the life of a 17-year old aboriginal youth who was passed out, intoxicated, behind the wheel of his Ford Mustang. Temperature at the nearby airport was -4.4 F, with a wind chill of -27.4 F. They could have arrested him for drunk driving, but since he was parked, they agreed to drive him home to his aunt and uncle’s house, where he was staying.

They recorded the youth’s name, the license plate, the location where he was parked (218 Tache Crescent), and the address where they dropped him off (1001 McCormack Road). Nobody – not Zakreski, nor the RCMP who would later investigate Neil Stonechild’s death, nor anyone else – would talk to him until 26 years later, when investigative journalist Candis McLean began to reinvestigate the events. It took her less than 10 minutes to track him down; she called directory assistance, gave them the name, and dialed the first number that came up. It was him.

Hartwig and Senger’s next call was to Trent Ewart’s complaint about a disturbance at the Snowberry Downs apartment complex, where Neil Stonechild was drunk and causing a ruckus. A computer check showed that Stonechild was UAL, with a warrant out for his arrest.

Brad Senger was a rookie constable, still on probation and trying hard to impress his fellow officers and superiors. Bringing in a wanted fugitive would have gone a long way to establishing his reputation as a good police officer – and keeping his job, since a probationary constable can be terminated at any time for any reason, or no reason.

Stonechild knew that he was wanted, however, so it would not have come as a surprise to Hartwig and Senger when they arrived at the Snowberry Downs complex to find him Gone on Arrival (GOA, in their police notebook shorthand).

At 4 minutes to midnight, Hartwig and Senger encountered Neil’s drinking companion, Jason Roy, three blocks south of Snowberry Downs, and pushed the “at scene” button on their in-car computer; this is known from police computer records. At the exact same minute – 11:56 pm – a woman named Shelley Grigorovich called 911 to report a prowler who matched Neil Stonechild’s description, 4 blocks to the east. Grigorovich and a friend, Darlene Nadeau, and their husbands had returned to the Nadeau house and had surprised the prowler lurking in the driveway. He ran off down the street, in the opposite direction from Snowberry Downs, with Mrs. Grigorovich chasing him for about a block. Darlene Nadeau, a trained insurance investigator, got a good look at him, and her description closely matched Neil Stonechild.

One minute later, at 11:57 pm, Hartwig and Senger ran a query on the name “Tracy Lee Horse”; this was a false name that Jason Roy gave to the police that night. It belonged to Jason Roy’s cousin, and Jason used it because he knew Mr. Horse did not have a criminal record.

Two minutes later, at 11:59 pm (one minute to midnight), Hartwig and Senger encountered another aboriginal male, Bruce Genaille. Genaille was Neil Stonechild’s cousin and bore a physical resemblance to him. Believing they had found Stonechild, Hartwig/Senger ran a CPIC (Canadian Police Information Centre) computer inquiry on Neil Stonechild to get a physical description. They continued to accuse Genaille of being Neil Stonechild until he produced his identification. Larry Hartwig wrote down the name “Bruce Genaille” in his police notebook, on the line after “Tracy Lee Horse”; this showed that he encountered Genaille after they spoke with Jason Roy.

Hartwig and Senger continued searching for Neil Stonechild at Snowberry Downs until 12:17 before reporting him as GOA. At 12:18, they were dispatched to look for a prowler at the home of Darlene Nadeau, in response to Shelly Grigorivitch’s 911 call. This prowler, who was very likely Neil Stonechild, was long gone, and at 12:27, Hartwig and Senger reported him GOA as well.

At 12:32, a perimeter alarm was activated at 2213D Hanselman Avenue, 3 miles northeast of where the Nadeaus lived, and 4 witnesses saw a prowler matching Neil Stonechild’s description. This alarm would be consistent with someone rattling doorknobs or shaking doors in an attempt to break in, to get out of the cold; that would have been consistent with Neil Stonechild’s previous behavior, according to his mother. Three miles in 36 minutes would be a speed of 5 mph, or an average jogging speed, so it is entirely possible that Neil Stonechild could have reached 2213D Hanselman Avenue in that time, especially if he was trying to put some distance between himself and the police.

According to Google Maps, a walking route from the Nadeau house at O’Regan Crescent to the field where Neil’s body was found several days later would most likely have taken him along the 51st Street overpass where 51st Street crosses the northbound exit from the Yellowhead Highway, with an estimated walking time of 1 hour, 15 minutes. If Neil was walking northbound at this time, he would have reached the overpass around 10 minutes past one; possibly later, since he might have been feeling the effects of hypothermia. An eyewitness – a bank manager who was driving northbound with his wife and infant daughter – saw a man matching Stonechild’s description at that location and walking northbound “sometime between 1 and 2 a.m.” In 2000, when the province ordered the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to reopen the investigation into Neil Stonechild’s death, this man gave a 12-page deposition to the investigators, including a hand-drawn map. He stated that he was convinced the man he saw was Neil Stonechild.

From there, following 51st Street east and then turning north onto Miners Avenue would have taken him to the Hudson Bay Industrial park and eventually onto 57th Street E. It is known, from Stonechild’s footprints, that he was on 57th Street and attempted to cross a snow-covered open field to 58th Street; possibly in an attempt to reach the Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems office building. He fell into a ditch that ran east to west; this is likely where he sustained the injuries to his face. With his last remaining strength, he managed to crawl back out of the ditch, but he was done. He died of hypothermia where he fell. His body was discovered 4 days later.

Unencumbered by any actual facts, Zakreski and Perreaux wrote story after story, strongly implying that Neil Stonechild had been sadistically murdered by the two police officers – Larry Hartwig and Brad Senger – who had been searching for him on the night he disappeared, even though the evidence clearly showed that they had not seen him that night and simply listed him as “GOA” – police notebook shorthand for “Gone on Arrival”.

In a foreshadowing of BLM, native activists – particularly the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations (FSIN) – began protesting these “documented” cases of “racist police murders”, putting enormous pressure on the government to find police officers guilty of wrongdoing.

Had Zakreski and Perreaux bothered to consult expert help, they would have come up with answers to their questions, but – not wanting to let the facts get in the way of a good story – they chose not to.

A decade later, at a provincial fact-finding inquiry into Neil Stonechild’s death, the presiding official – a retired judge named David H. Wright – would indulge in some very specious rationalizations, cherry-picking and assumption of facts not in evidence to find that Constables Hartwig and Senger had driven Stonechild to the industrial park in the north end of the city and subsequently lied about it, and to justify his exclusion of a significant body of evidence negating that conclusion. Wright’s ruling, which was arrived at by an informal process that lacked judicial safeguards and denied Hartwig and Senger the due process they were entitled to, was probably the single greatest factor in the public’s acceptance of Zakreski and Perreaux’s lunatic conspiracy theory.

A conspiracy theory takes off

Zakreski’s wild conspiracy theory didn’t just grow legs; it sprouted wings and took off.

Amnesty International, a leftist organization which had long ago abandoned its original mission of freeing and supporting prisoners of conscience in third world hellholes in favour of finding fault with western police officers using Tasers™ to apprehend fleeing criminals, took up the cause. In 2001, based solely on Zakreski’s reporting, they listed “reports”, “allegations”, and “claims”, stating that Saskatoon police

“had an unofficial policy of abandoning intoxicated or troublesome members of the indigenous community away from the population centre of Saskatoon, thereby placing them at great risk of dying of hypothermia during the winter months. … First Nation member Darrell Night claimed that in January two Saskatoon police constables … drove him outside the City and abandoned him in freezing conditions. He only survived because he was able to get help from the nlghtwatchman of a nearby power station.”

Somehow, the phrases “abandoned him in freezing conditions” and “nearby power station” don’t seem to go together; however, Amnesty International had no problem with the wording.

Now humiliated on the international stage, and facing pressure from the FSIN (Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations), the Saskatchewan government seemed determined to clear out the rot in the Saskatoon Police Services, whether it existed or not.

Sending two decorated police officers, Ken Munson and Dan Hatche, to prison for a humanitarian gesture – giving an indigenous man a break by not charging him for drunk and disorderly – was a start. But they needed to prove to the voters that they were serious about dealing with “police racism”.

They launched “Operation Ferric” and enlisted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Canada’s only federal police force, to get to the bottom of the scandal.

RCMP investigators appear to have gone into the investigation with the preconceived notion that their brethren in the SPS had committed inexcusable crimes, and that it was their duty as police officers to ensure they were exposed for what they were. The possibility that the media and the politicians had gotten it wrong seems not to have occurred to them.

For example, Darlene Nadeau, a trained insurance investigator, saw Neil Stonechild – or someone closely matching Stonechild’s description – at 118 O’Regan Crescent at the exact same minute that Jason Roy claimed he was in the back of Hartwig and Senger’s cruiser. Stonechild could not have been in two places at once; if it was Neil Stonechild that the Grigoroviches and Nadeaus saw that night, then Jason Roy – who had been convicted four times of lying to the police, and who admitted lying to the police that night – was either lying or mistaken. RCMP Staff Sergeant Lyons interviewed Darlene Nadeau regarding what she had seen. She told him that when the prowler had stood up, his feet got tangled in a bush and he had to catch his balance; that was why she had gotten such a good look at him. Staff Sergeant Lyons did not mention this in his summary. Nadeau also was adamant that the prowler was not dressed appropriately for the weather; he was only wearing a light jacket, which was open because she could see he had on a shirt of a contrasting colour. (Neil Stonechild was wearing jeans, a jean jacket with a red lumberjack shirt underneath, and running shoes.)

Staff Sergeant Lyons’s summary stated:

- The Nadeau driveway was long and narrow. (False; not only was this untrue, neither Darlene Nadeau nor Shelly Grigorovich said anything of the sort.)

- The RCMP summary stated the person was “wearing a jean jacket or light coat and looking cold”. (Again, False. Darlene Nadeau was adamant that the prowler was not wearing a coat. In fact, when Lyons had asked, during the interview, “It wasn’t a heavy coat, at any rate?”, Nadeau had reiterated “No. The feeling I have strong is that it was not appropriate wear for the winter, but it was a jacket of some type.” But Lyons described it as a coat anyway.)

- The summary omitted several key points, including the fact that the intruder had straight black hair past his shoulder (a match for Neil Stonechild), and that he was wearing a shirt of a contrasting colour (Neil was wearing a red lumberjack shirt under his jean jacket);

MR. JUSTICE DAVID WRIGHT'S FACT-FINDING INQUIRY137. Every one who, with intent to mislead, fabricates anything with intent that it shall be used as evidence in a judicial proceeding, existing or proposed, by any means other than perjury or incitement to perjury is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding fourteen years.

Criminal Code of Canada (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46)

Executive Summary: Facing pressure both internationally and from the FSIN, the province appointed a retired judge, David Wright, to conduct a fact-finding inquiry into the death of Neil Stonechild. This was not a court, and consequently it lacked the safeguards of a trial. For example, it was entirely up to Mr. Wright to decide what evidence to allow and what evidence to disallow.

Because of this, Wright’s mandate expressly prohibited him from laying blame; his role was purely to determine how and why Neil Stonechild froze to death and present recommendations on how to prevent future tragedies. Wright disregarded the prohibition against laying blame and declared that two Saskatoon police officers, Constable Larry Hartwig and Constable Brad Senger, had kidnapped Stonechild, driven him through the city to the north end, and abandoned him to freeze to death.

In order to reach this conclusion, Wright invented facts that were not in evidence, ignored a large body of evidence that would have showed his conclusions to be wrong, cherry-picked evidence that supported his conclusion, and based his finding entirely on the decade-old memory of a career criminal and four-time convicted liar, Jason Roy.

Because it was not a trial, Constables Hartwig and Senger were powerless to call witnesses or present evidence of their own to challenge Wright’s conclusion. Despite this, the media treated Mr. Wright’s conclusion as proof of the police officers’ guilt. Both officers were fired, and falsely branded by the mainstream and social media as racist murderers, despite a complete lack of any credible evidence to that effect.

—–

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock Holmes – A Scandal in Bohemia)

On paper, the Honourable Mr. Justice David Henry Wright was ideally suited to conduct a fair and impartial inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the November 1990 death of Neil Stonechild, the task to which he was appointed in 2003.

In 2003, Wright graduated from the University of Saskatchewan law school in 1955. The following year, he passed the Saskatchewan bar exam the following year, and joined the firm of MacDermid & Co. Four years later, he was a senior partner. He was appointed a Justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench of Saskatchewan in 1981. He taught Civil Procedure and Ethics as a regular faculty member at the U of S College of Law in 1982.

Mr. Wright obviously must have known that “assuming facts not in evidence” is a valid objection in any court of law; yet he himself assumed facts for which there was no supporting evidence, and considerable negating evidence. Specifically, in order to discredit and justify his rejection of Bruce Genaille, a crucial eyewitness, he invented a disturbance at a 7-Eleven convenience store on the night that Neil Stonechild died. There was no evidence of this disturbance; no 911 call was recorded, no police were dispatched to the convenience store, and no eyewitnesses to the alleged disturbance were called to testify.

Major thesis

Under intense pressure from the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations, and international scrutiny because of the Amnesty International reports, the government of Saskatchewan had a compelling interest in showing that Saskatoon police officers had been criminally responsible for Neil Stonechild’s death on the night of 24/25 November 1990. The evidence that Constables Hartwig and Senger had picked up Stonechild, driven him to a remote industrial park in the north end of the city, beaten him badly, and left him there to die, consisted entirely of the ten-year old recovered memory of Neil Stonechild’s drinking companion that night. Ten years had passed; Jason Roy was now a career criminal with a lengthy rap sheet, including armed robbery, kidnapping, home invasions, and four convictions for lying to the police. Hartwig and Senger had encountered Roy at 11:56 pm, when they arrived at Snowberry Downs

Roy admitted that he had given Hartwig and Senger a false name – Tracy Lee Horse. That name does not even contain the letter “J”; yet Roy says that Stonechild was sitting in the back of the police cruiser, “gushing blood” from his face, with his hands cuffed behind him, and that Neil was screaming “Jay, Jay, they’re going to kill me.” Yet the Honourable Mr. Justice Wright never wondered why two trained police officers would completely ignore the fact that their prisoner was addressing “Tracy Lee Horse” as “Jay”.

There was no blood found on Neil Stonechild’s clothing; yet Mr. Wright never questioned how a man sitting down, with his hands cuffed behind him, and blood “gushing” from his face, could avoid getting blood on his clothing.

A few minutes after speaking with Jason Roy, aka “Tracy Lee Horse”, Constables Hartwig and Senger stopped and spoke to Neil’s cousin, Bruce Genaille. Genaille testified at the inquiry that they spent about ten minutes questioning him, before he convinced them he was not Neil Stonechild (to whom he had a strong family resemblance). Genaille testified that there was nobody in the cruiser when he spoke with Hartwig and Senger. Mr. Wright concluded – with absolutely no supporting evidence – that the encounter between Mr. Genaille and the two constables had actually taken place an hour earlier, and that the police officers had waited an hour before thinking to query “Bruce Genaille” on their vehicle-mounted computer terminal.

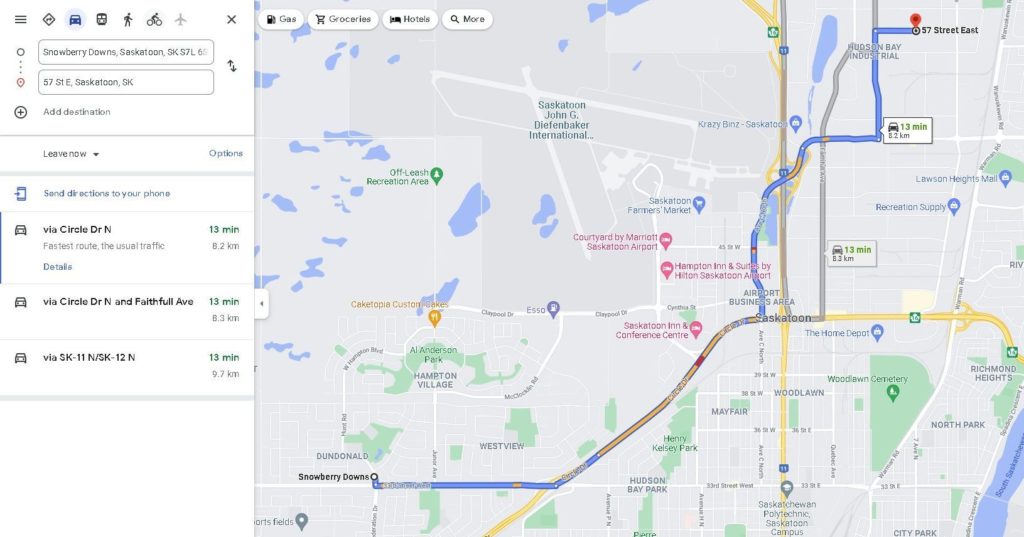

Google Maps: Driving routes from Snowberry Downs to location of Neil Stonechild’s death

November 24, 1990

10:59 pm Hartwig and Senger, working together for the first time, are called to investigate an intoxicated native man who is passed out in his car at 218 Tache Crescent. They drive him home to 1001 McCormack Drive. According to Google Maps, this would require 7 minutes driving time.

11:08 pm (approximately) Hartwig and Senger deliver the intoxicated man to his aunt and uncle’s home at 1001 McCormack Drive.

From McCormack Drive to the 7-Eleven would take another 10 minutes driving time.

Approximately 11:18 or later: According to Wright, Hartwig and Senger encounter Neil Stonechild’s cousin, Bruce Genaille, and spend – according to Genaille’s testimony – at least ten minutes questioning him in the belief that he is Neil Stonechild.

Problem: Why would the two officers be questioning Mr. Genaille about Neil Stonechild at 11:30 pm, when they would not be asked to look for Stonechild until twenty minutes later?

11:49 p.m. Trent Ewart’s telephone complaint received by the Saskatoon Police Service

11:51 pm Car 38/Cst. Hartwig and Cst. Senger acknowledge the call and report that they are en route

Wright “concludes” that Hartwig/Senger encountered Stonechild shortly after 11:51 pm and placed him in their cruiser. He gives no justification for this conclusion.

The cruiser proceeded a short distance down a lane to Confederation Drive. As the car exited the lane, the police intercepted Jason Roy.417 Roy observed Stonechild in the rear of the cruiser. When asked if he knew the prisoner, he denied that he did. Roy testified his friend was cursing him and calling for help and telling Roy to tell the police who he was.

Wright pointedly fails to mention that Neil was allegedly addressing Roy by the name “Jay”, even though Roy had given the false name “Tracy Lee Horse”; the police allegedly did not find it curious that their alleged prisoner was calling Tracy Lee Horse by the name “Jay”.

11:56 pm Cst. Senger conducted a CPIC computer inquiry on the name “Tracy Lee Horse”.

11:56 pm Four blocks away, Shelly Grigorovich makes a 911 call to report a prowler matching Neil Stonechild’s description. Wright makes no mention of this in his conclusion.

11:59 pm Cst. Hartwig conducts a CPIC query on the name “Neil Stonechild”.

November 25, 1990

12:04 am Cst. Hartwig conducts a CPIC query on the name “Bruce Genaille”.

12:17 am Hartwig and Senger report Stonechild GOA (gone on arrival)

12:18 am Hartwig and Senger are dispatched to respond to Shelly Grigorovich’s 911 call regarding a prowler at 118 O’Regan Crescent.

12:24 am Six minutes later, Hartwig and Senger arrive on-scene at 118 O’Regan Crescent. Google maps estimates 2 minutes driving time to 118 O’Regan Crescent.

12:27 am Hartwig and Senger report prowler GOA

12:30 am Cst. Senger conducts CPIC inquiry of Trent Ewart.

Mr. Wright concluded that there was a 27-minute gap, which Constables Hartwig and Senger could not account for, between the time they spoke with Jason Roy (11:56 pm) and the time they arrived at their next call, at 118 O’Regan Crescent (12:24 am).

There are two problems with this.

First of all, the 27-minute gap only exists because Wright chose to explain away the ten minutes that Hartwig and Senger spent talking to Bruce Genaille, by conveniently inventing a phantom disturbance call at the 7-11 convenience store at the corner of 33rd Street West and Confederation Drive.

Second, why would Hartwig and Senger be questioning Bruce Genaille about Neil Stonechild, half an hour before they were dispatched to look for him? What evidence did Wright have that they encountered and questioned Genaille at the 7-Eleven store between 11:18 and 11:51?

Third, the Google Maps estimated driving time from Snowberry Downs to the field where Neil Stonechild’s body was later found is from 12 to 14 minutes. This would mean Hartwig and Senger spent:

- 12 minutes to drive Neil Stonechild through the centre of Saskatoon to the field between 57th and 58th Street;

- 3 minutes to drag Stonechild out of the car, halfway across a snow-covered field, leaving only one set of footprints and no drag marks, and beat him until he was dead, unconscious, or unable to move; and

- 12 minutes to drive back to O’Regan Crescent for their next call

all for the rather questionable thrill of throwing racial insults at, and murdering, a 17-year old boy who’d had too much to drink.

Other Testimony

Dr. Emma Lew: From the Wright report:

Dr. Emma Lew is a Forensic Pathologist attached to the Medical Examiner’s office of Dade County, Miami, Florida, and has held that position since 1992. She was born in Saskatoon and attended the University of Saskatchewan and served her internship at St. Paul’s Hospital. She completed her residency in anatomical pathology at the University of British Columbia and at the University of Saskatchewan and obtained a forensic pathology fellowship from the Dade County Medical Examiner’s office from 1991 to 1992. She is also an Assistant Clinical Professor of Pathology at the University of Miami School of Medicine. She has published a number of articles and lectured.

So Dr. Lew was not only extremely well-qualified; she was born and brought up in Saskatoon and was familiar with the weather and temperatures that accompanied living in Saskatchewan. She

Commission Counsel had not intended to call Dr. Lew but was strongly urged to do so by Counsel for the Saskatoon Police Service and others.

Why would the Commission Council not want an expert with Dr. Lew’s impeccable credentials to testify? Why did the Council for the Saskatoon Police Service have to “strongly [urge]” the Commission Counsel to do so?

Wright was seemingly determined to prove that the parallel wounds on Neil Stonechild’s nose and feet were caused by a pair of police handcuffs. Dr. Lew testified that it would be very difficult to inflict those wounds with a pair of police handcuffs:

- Yes. The edges of the bracelet of a handcuff are relatively smooth. There is

one area on the interlocking part of the handcuff where there are teeth.

Those edges are jagged. However, the spacing between the abrasions on

the nose and the spacing between the – the teeth on that particular portion

of the handcuff are not the same. And if you were to look anywhere else on

the pair of handcuffs, it is not possible for handcuffs to produce those linelike,

fairly superficial but fairly thin and straight line-like scrapes.”

…

“A. …An abrasion of this sort is made by a relatively sharp edge. The blunt edge of the metal bracelet will not cause an abrasion. Sure, the bracelet of a handcuff is very capable of causing other injuries, but those injuries would be more blunt-force type.

In other words, if you were struck with any other part of the handcuff except for those teeth, and struck with enough force, you would get a bruise, you could get a cut or what we call a laceration, which is a tear of the skin, and with enough force you can break the nose. But, as I said before, all other parts of the handcuff are smooth apart from these little teeth which are capable of causing the scrapes or abrasions.”

Lew testified that a fall into vegetation was more likely the cause of the nose injury.